June 4th is the birth date of a beloved member of my family, and I’d prefer to remember it solely as such.

However, it’s also the anniversary of the massacre in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square against student demonstrators – an event that’s been a milestone in my life for many reasons. For me it’s difficult to not remember that time without pangs of sadness, anger and a resolve to not let the event disappear from world consciousness.

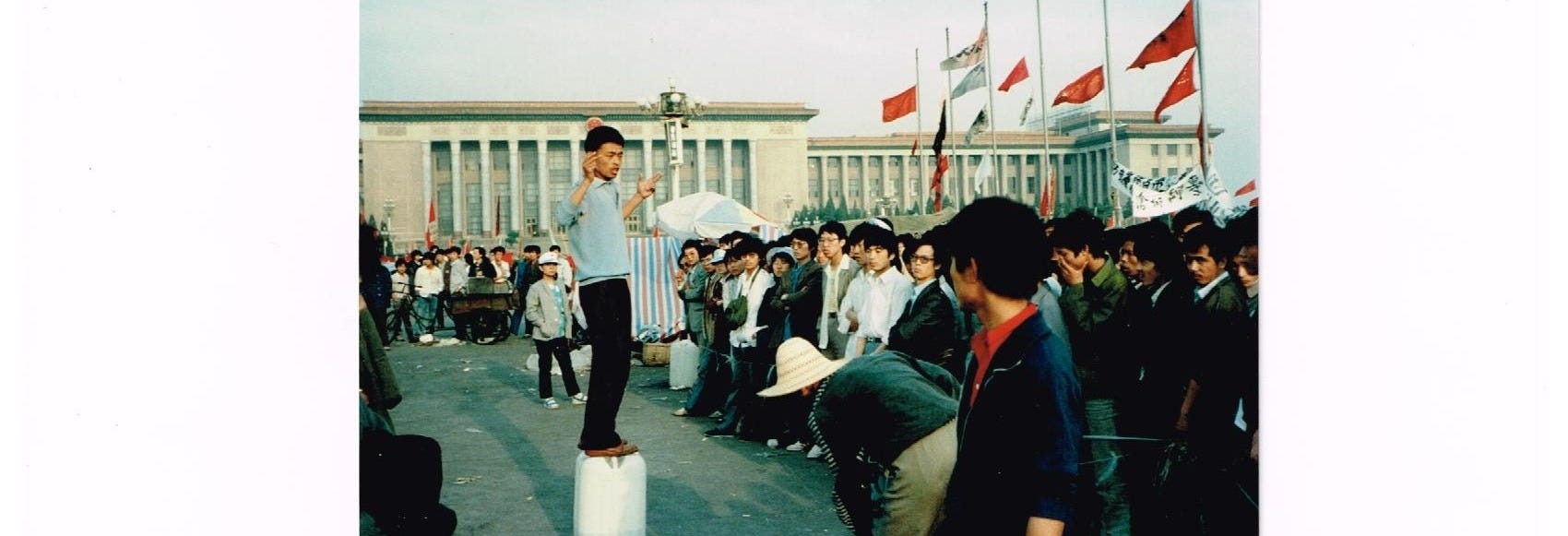

Over the years I’ve written about my experiences during the demonstrations and subsequent crackdown for several media outlets. I also have scores of pictures that I shot during my time there. I want to share some of those images with you now.

In the spring of 1989, I was a producer for a major news network in New York. I had been watching the student demonstrations in Beijing with a combination of fascination and frustration.

I was a Chinese history major in college, and it was obvious that what was occurring in the Chinese capital and in other Chinese cities was historic. Hundreds of thousands of people marching in the streets, demanding an end to government corruption and access to more democratic forms of government. I’d later hear some of the students in the square refer to it as an ài guó yùn dòng, a patriotic movement.

I was new to the company, and one morning had sent the international desk my resume and some other information; letting them know I’d be very happy to assist in any way with their coverage of the event.

Later that day, my bureau chief banged open the glass door of the video editing booth where I was working.

“What the hell have you been telling the international desk?” he fumed. “They want you on a plane to Beijing tonight.”

By the next morning I was in San Francisco airport, waiting on a flight to Hong Kong – where I met up with some of my colleagues, who had also flown in from all over the world.

We had to fly into Hong Kong for a day’s stopover, on our way to Beijing, to get our visas approved. Journalists could not get visas at the time due to the unrest, so most of us went in as television “producers”. Our hotel in Hong Kong overlooked Victoria Park on Hong Kong Island, and I went down to the park as I noticed crowds gathering.

It was a demonstration of Hong Kong high school and university students, showing their solidarity with the demonstrations up north in Tiananmen.

That evening I watched from my hotel window as the candlelight vigil in the park grew from a trickle of young people into tens of thousands of demonstrators.

Victoria Park was the site of memorial demonstrations every June 4 after the massacre.

Several years ago, however, after taking control of Hong Kong from the British, the Chinese government put a stop to the annual Tiananmen vigil in Victoria Park.

Upon our arrival in Beijing we were taken directly from the old Beijing airport to Tiananmen by our colleagues, who asked us how the story was being received outside of China. I remember the electricity of walking into the heart of the square and being surrounded by demonstrators – most of whom were students.

Many of the demonstrators had been living in the square for days, and had accumulated huge piles of debris. Weeks of uncollected trash littered the square as well as the Monument to the People’s Heroes, an obelisk in the center of the Square that was also the epicenter of the student demonstrations.

A lot of the demonstrators were camped out in the Square, sheltered by little more than sheets of plastic strung up on makeshift tent poles. At one point a Hong Kong group donated some “pop-up” tents for the demonstrators, which apparently improved conditions somewhat.

The Square was filled with students from universities and academic institutions all over China. Here are some out-of-towners studying a Beijing street map.

The students were aware the whole world was watching the situation in the Square. This English-language sign underscored their attempts to engage the global audience that was intently watching the situation in Tiananmen unfold.

Demonstrators applauded groups from different universities and organizations as they paraded on Chang’an Avenue, on the northern side of Tiananmen.

Tens of thousands of additional people filled up Tiananmen on weekends during the demonstrations, lending their support, satisfying their curiosity or just enjoying the festival atmosphere. At this point the student leaders had cordoned off the Monument to the People's Heroes, as they awaited food donations from supporters.

Weekends brought the curious to Tiananmen, as well as some of the more lighthearted demonstrations. One Sunday morning, a flatbed truck drove around the perimeter of the square, while drummers in the back of the truck beat out rhythms. In this picture you can sort of see one of the drummers, with his sticks raised, while accepting the crowd’s applause.

The view from our balcony on the 11th floor the Beijing Hotel, our “forward base,” looking westward on Chang’an Avenue, with Tiananmen Square partially seen in the top of the picture. That room was a mess because we didn’t let the hotel staff – all government employees – come in to clean it. It was from this balcony that we later videotaped the famous “tank man” sequence that was seen around the world.

In 2019 Kevin Shanley, a policy analyst at the Asia Society Policy Institute, wrote about the CCP’s ongoing campaign to expunge the Tiananmen Square protests and their violent suppression from both Chinese history “and the minds and memories of the Chinese people.”

“To this very day,” Shanley continued, “the Chinese government has never apologized to the victims, or their families, of this brutal political crackdown. Instead, the leaders in Beijing have tried to spread two separate narratives to two separate audiences. To the Chinese people, they say this event never happened. They want the rest of the world to believe it was fault of the students who only got what they deserved.”

Shanley noted that every year, as the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown approaches, its potential commemoration “is greeted with anxiety, even trepidation in Beijing. It is simply amazing that this self-described ‘incident’ in Chinese history could still stoke such fear among the Chinese leadership.”

Let’s see what this year brings.